I recently came across an amusing subhead in a promotional flyer: “Learn from Incredible Speakers.” Then the piece promoting an all-day conference said, in smaller print, “Listen to expert speakers from around the country.” Ah, “expert.” Nice recovery, but, unfortunately, what you told me in bold print was that the speakers are not to be believed. And I need to pay to hear them?

This lapse in how to express that the speakers are really good prompted me to make a few unrelated observations about “good” and “bad.”

Doing “good”

In conversation, if we’re asked how a presentation was, we might favorably respond “Good!” or “Tremendous!” or even “Incredible!” and sell our commonplace answer with enthusiastic body language and inflection. But in writing, where our words are out there on their own and we want to strive for more freshness and precision, we can improve on our personal clichés by dipping into our synonym bank.

Think of all the choices we have when we want to emphasize “good”: “superb,” “fantastic,” “exceptional,” “remarkable,” “wonderful,” etc. And we can often call upon more exacting descriptive words: a “stunning photo exhibit,” an “agile mind,” an “electrifying speaker.”

Other descriptors get into the why something is “terrific” or “extraordinary”: a “tireless volunteer,” a “savvy consultant,” an “eye-opening lecture,” “ingenious choreography.”

We know that continually bulking up our vocabulary arms us with ever-increasing options in how we express ourselves, and there might not be an easier place to start than expanding all the ways we can say “good.”

“Good” vs. “well”

Two reminders about this adjective and the corresponding adverb:

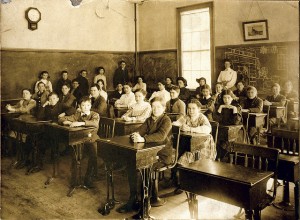

1. Sometimes we hear or read misuses like these: He did good to break even. So far, she’s doing especially good in math. After the tuneup, the car ran good. Ouch. Ugly errors like those are bound to distract. Let’s go with the adverb, “well.” He did well. She’s doing especially well. The car ran well.

2. But remember that we can’t go wrong when referring to how one feels. I feel good. I feel well. She is good. She is well. Our grammar rules would seem to dictate that only “good” is correct, but when the context is health, “well” is correct too.

“Bad” vs. “badly”

Examples of the main trap regarding this pair are I feel badly for my neighbor or I feel badly about your loss. A few verbs like “is,” “are,” “were,” “seem,” “appear,” and “feel” are linking verbs. They don’t express action; they just … well, link. So saying or writing, I feel bad is correct because that’s like saying or writing I am bad or It seems bad. We’d never say or write I am badly or It seems badly. So let’s stay away from the ugly I feel badly.

Postscript: One of my early posts (http://www.normfriedman.com/blog/wp-admin/post.php?post=73&action=edit), focusing on the overuse of “very,” complements this post. You might want to check it out.

In addition to presenting workshops on writing in the workplace, Norm Friedman is a writer, editor, and writing coach. His 100+ Instant Writing Tips is a brief “non-textbook” to help individuals overcome common writing errors and write with more finesse and impact. Learn more at http://www.normfriedman.com/index.shtml.